The Clean Power Plan, part 2

Like seemingly everyone else in the entire state of Maine, I found it difficult to get much work done during the summer. So, although I said in my most recent post that I would write more about the proposed Clean Power Plan, it’s taken a bit longer than I thought. I know you’re all waiting with bated breath….

In my most recent post, I discussed some of the details of the proposed Clean Power Plan. Since then, after analyzing comments from stakeholders and constituents from around the country, the plan has been updated. The final version allows for significantly more flexibility than the proposed version in how states measure and achieve compliance, pairs the rule with incentive programs, and requires states to address grid reliability in their compliance plans. Click here for details.

However, that’s not what I wanted this blog post to be about. I wanted to focus on the benefits of the rule for the state of Maine.

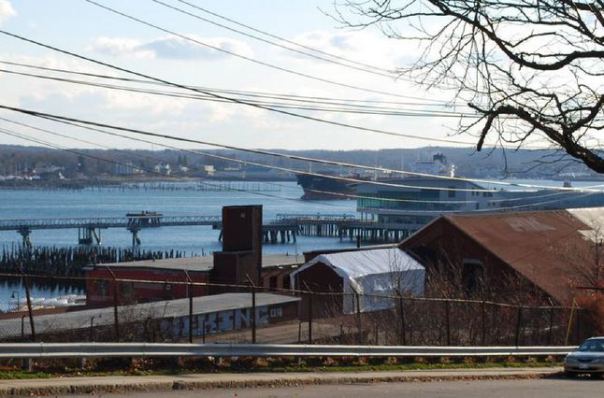

Maine has sometimes been called the tailpipe of America, given its position downwind of Midwestern industrial states and of the northeast metropolitan corridor. These airborne emissions from factories and from coal-fired plants contain not only carbon dioxide, but sulfur dioxide, mercury, and particulate matter, among other contaminants. These contaminants can wreak havoc on people’s lungs, heart, and overall health, as well as contribute to ground-level ozone, obstructing many of Maine’s most iconic views.

Any halfway decent benefit-cost analysis of the Clean Power Plan, then, has to include a measure of the benefits that will accrue to Maine through “avoided emissions.”

Here’s the way an environmental economist would go about it. First, engineers would need to estimate by how much each “affected facility” would be able to reduce its emissions of various contaminants. Although this seems like a daunting task, it can be done. One way to do it is to predict how a typical facility will respond to the regulation (by reducing its output, changing its fuel use, or installing new pollution reduction equipment). Then, those engineers would need to estimate the reduction in emissions that would result. While firms in Maine will not be affected by this rule to the same extent as firms in other states (see my previous blog post), states upwind of us will. It’s the reduction in those emissions that’s the most significant to Maine.

Second, another set of scientists would need to run that data through a “fate and transport” model. The idea here is that different contaminants, once they’re released into the atmosphere, behave in different ways. Some, like carbon dioxide, are what we may call “uniformly mixed pollutants.” In other words, once they’re released, they immediately disperse into the atmosphere. Others, like sulfur dioxide or particulate matter, are local pollutants. They tend to stick around in the general vicinity where they’re released, depending on things like the prevailing wind direction, the height of the “stack” (or chimney) from which they were released, or the “exit velocity” (the speed at which they were released). And, as anyone who’s studied any chemistry knows, some contaminants have a longer half-life than others, and some may even degrade into more harmful chemicals than at first, or even combine with other chemicals to form more dangerous compounds.

Once this is done (and scientists do have sophisticated models that can allow them to study this in detail), we can tell with a reasonable degree of certainty, what type of contaminants (and how much) will NOT be falling on Maine as a result of this rule. Generally, we can expect to see a reduction in the following contaminants: particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and, of course, carbon dioxide.

Finally, we can link that data with the probable health effects associated with those contaminants. That’s (finally) where an environmental economist would come in.

For example, Maine has the highest asthma rate (for adults) in the country. For children, Maine’s asthma rate is among the highest (10.7% of Maine children have asthma, compared to 8.9 % nationally.)

Asthma is caused by a number of different factors, but it is aggravated by “particulate matter,” or small particles that are emitted from the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and other substances. These particulates can lodge in the lungs, making it difficult to breathe.

So, what are the economic effects of a high asthma rate? Economists tend to measure the direct costs ( doctors’ visits, medications, hospitalization, etc.), as well as the opportunity costs (days taken off from work to spend with a sick child, etc). That can add up quickly. More difficult to measure, but no less significant, is lost productivity. How much more economically productive could someone be, if she didn’t have a respiratory disease that – literally – slowed her down?

Particulate matter is also associated with reduced lung capacity, nonfatal heart attacks (which actually can be fatal in people with pre-existing conditions), and irritation of the airways. And these are only the health effects. Particulate matter is increasingly a problem when it combines with sunlight to produce ground level ozone, which decrease your enjoyment of the view from Mt. Katahdin, or when it is deposited in Maine’s lakes or streams, changing their basic chemistry and affecting the integrity of the ecological system.

And this is just one contaminant. Other contaminants likely to be reduced include, as stated, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides. Add in those costs of human diseases health effects and other ecological damages related to these contaminants, and we’re talking real money.

This is the biggest problem that I see with passing reasonable, beneficial environmental regulations. Those opposed to such regulations have a wealth of data at their fingertips detailing the costs of compliance. It’s very easy to show that complying with a certain regulation (installing pollution control technology, for example, or using a more expensive but “cleaner” production process) will cost money, or jobs. Less simple is detailing the benefits of reducing harmful pollution. And for some, that difference could literally be a matter of life and death.